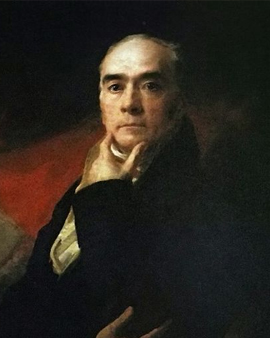

Every movement ignites a counter movement. The ideas of the Enlightenment around 1750 sparked such a fierce political hullabaloo (American independence, French Revolution, Napoleon's endless wars) that many contemporaries turned away angrily and fled into "Romanticism". Scotland, too, produced a Romantic painter of distinction, Henry Raeburn, just at that time.

Born in 1856 in Stockbridge on the River Leith, he first learned the craft of a goldsmith's assistant, who discovered and encouraged Raeburn's talent for painting. One of his first portrait models was Ann Edgar, widow of Lord Leslie - a few months later she was Raeburn's wife. The marriage provided Raeburn with the financial means to further his education in Edinburgh and in Italy. Back in Scotland, Raeburn took off. There is hardly a contemporary Scottish personality who has not been portrayed by him over the years - right up to the famous poet Sir Walter Scott in 1822. It was considered a status symbol, so to speak, to be painted by Henry Raeburn. His portraits worked primarily with the play of light and dark - a subject that we Central Europeans automatically associate with Rembrandt. His artist colleagues rather compared Raeburn to Goya... But an unevenly lit background was perfectly normal at a time when neither gas lighting nor electric light bulbs were known. Most portraits were painted in the glow of oil lamps or fireplaces - simply because there were no other light sources.

Raeburn's fame outside of Scotland was and still is rather limited because he became a teacher and founder of the "Scottish School". Although also celebrated by the English art world, Raeburn travelled to London only rarely and for a short time and never moved there. He was and remained a Scot, a man from Edinburgh - and it is this steadfastness that has given Scottish painting a certain independence to this day. As is well known, the inhabitants of Scotland are still first Scots and only then British - and in the decades after the Jacobite uprising and the Battle of Culloden (which dealt the Highland clans the deathblow), even between the Edinburgh of the loyal Lowland Scots and London there was an even greater distance than "only" 800 kilometres...

Raeburn was elected president of the Scottish Artists' Association in 1812; in 1815 he became a member of the Royal Scottish Academy. When King George IV travelled to Scotland in 1822 (as the first British monarch for two centuries), Raeburn was knighted and appointed "Painter to the King in Scotland". Raeburn died in 1828 and is buried on the outer wall of Saint Cuthbert Church in Edinburgh.

×

_-_(MeisterDrucke-901195).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-901195).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-261784).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-261784).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-97341).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-97341).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1630144).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1630144).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1628838).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1628838).jpg)

_circa_1790-1800_(oil_on_canvas)_-_(MeisterDrucke-1209868).jpg)

_circa_1790-1800_(oil_on_canvas)_-_(MeisterDrucke-1209868).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

engraved by C Turner 1843 (mezzotint) - (MeisterDrucke-59983).jpg)

engraved by C Turner 1843 (mezzotint) - (MeisterDrucke-59983).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1630501).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1630501).jpg)

_1815_-_(MeisterDrucke-377213).jpg)

_1815_-_(MeisterDrucke-377213).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1630309).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1630309).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1630318).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1630318).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

c1819 - (MeisterDrucke-156078).jpg)

c1819 - (MeisterDrucke-156078).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_c1810_-_(MeisterDrucke-52693).jpg)

_c1810_-_(MeisterDrucke-52693).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-664761).jpg)

- (MeisterDrucke-664761).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-179527).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-179527).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1454980).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1454980).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

from National Portrait Gallery volume III published c1835 - (MeisterDrucke-57778).jpg)

from National Portrait Gallery volume III published c1835 - (MeisterDrucke-57778).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1128089).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1128089).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

by Henry Raeburn - (MeisterDrucke-23290).jpg)

by Henry Raeburn - (MeisterDrucke-23290).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1118311).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1118311).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_oil_on_canvas)_-_(MeisterDrucke-1132880).jpg)

_oil_on_canvas)_-_(MeisterDrucke-1132880).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-901196).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-901196).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1562700).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1562700).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_Baronet_of_Calderwood_Painting_by_Henry_-_(MeisterDrucke-1103909).jpg)

_Baronet_of_Calderwood_Painting_by_Henry_-_(MeisterDrucke-1103909).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1456035).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1456035).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1097302).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1097302).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1097735).jpg)

_-_(MeisterDrucke-1097735).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)